Andrew Murstein President, Medallion Financial

Andrew Murstein President, Medallion FinancialAndrew Murstein knows a thing or two about the American Dream. When his grandfather Leon came to this country from Poland in the 1930s, he brought little with him beyond a drive to make a better life for himself. To this end, he started his own company with a single taxi license in 1937. It cost him $10 and he drove the cab himself.

By the 1970s, that single cab had turned into a fleet of nearly 500. At 42, Murstein, together with his father Alvin, runs the company his grandfather founded; and as president of the New York’s Medallion Financial, has taken one man’s dream, and turned it into a vehicle for hundreds more.

It was in 1979, Murstein explains, that the successful taxi business made its initial transition into commercial lending. “When my father got involved in the business, he wanted to sell some [taxis] to take some chips off the table and no banks would provide financing for the buyers of those medallions so he had to take back the paper himself,” he says. “That’s how our finance company started.”

Today, the company’s motto, “In Niches There Are Riches,” could not be more relevant. Since his father’s foray into commercial finance, Medallion has launched two new units and an industrial bank. The company went public in 1996, and trades on the Nasdaq under the ticker symbol TAXI.

But the company makes its bread-and-butter in an industry few outside the transit world are aware exists. Most of us have seen the little metallic plaque on the front of taxicabs, but few understand exactly what it represents.

For a taxi owner, a medallion is like a ticket to the big time. Drivers save for years to get one, and having one means no longer paying a flat rate to drive someone else’s cab for 12 hours a day. Medallion Funding, the company’s taxi lending arm, offers financing to both fleet operators and single cab owners.

The medallion system was created in 1937 when New York’s Board of Aldermen adopted the Haas Act, which placed a moratorium on the issuance of new taxicab licenses. According to Bruce Schaller, a former industry consultant who now serves as New York’s Deputy Commissioner for Planning and Sustainability, the system was crafted to address an overabundance of taxis that had depressed driver earnings and congested city streets.

Beyond placing a cap on medallions, the Hass Act provided for the automatic renewal of vehicle licenses and allowed for the transfer of licenses between owners. “This transferability provision was vital to the subsequent establishment of license values,” Schaller writes in his article, “Villain or Bogeyman, New York’s Taxi Medallion System.”

A provision that would have allowed the city to issue additional medallions was repealed in 1971; as a result the value of the licenses has continued to grow exponentially.

“Taxi medallions have been maybe the best investment to own in the United States over the past 70 years — they’ve outperformed the Dow Jones, the Nasdaq, real estate, gold, almost every major index you can think of,” says Murstein.

While the Dow has gone up 8% per year over the last 50 years, taxi medallions have gone up almost double that at 14% per year.

Since the company began lending in 1979, Medallion has facilitated more than $900 million in loans to this specific segment and, what’s more, boasts that it has never had a loss.

In 2007, the company reported net earnings of $15.4 million, an 18% increase over 2006. Medallion’s on-balance sheet taxicab medallion loan portfolio increased 16% to $498 million last year, from $428 million in 2006, and $375 million at year-end 2005. “People assume that it’s not a growth business but our track record obviously shows the opposite,” says Murstein.

In fact, despite dealing with a finite asset base — a number that hasn’t changed in 70 years — Medallion Financial has managed to grow more than 20% a year for the past five years. Murstein says Medallion employs several strategies.

“For one there is the ever expanding value of the medallion,” he explains. “Just like home equity loans, when somebody’s home equity increases over time you’re going to take out a loan against it, here guys tap into the equity of their medallions.”

And like real estate, the value of taxi medallions has grown considerably; 30 years ago the roughly 12,000 medallions circulating in New York had a collective value of $800 million, today those same medallions are worth $7 billion, Murstein says. In May 2007, the price of a single corporate medallion hit an all-time record high of $600,000. Owner/operator medallions, which are issued to people who drive their own cabs, are a little cheaper — currently trading at around $425,000.

“So as that balloon gets bigger and bigger we can grow our company just by lending more against the current owners that are customers of ours and their current medallions,” Murstein explains.

At the same time, he says the company, which spent the past three decades focused on New York City, has recently been expanding into new markets. Today, in addition to New York, Medallion offers loans in Miami, Boston, Chicago, Newark, Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Finally, Medallion works aggressively to usurp market share from its competitors. “We’ve been very effective at that, we set up our own bank several years ago to lower our cost of funds and were able to take away market share from other lenders in the business.”

Not that there’s much competition to worry about, though. “Banks have never really financed this industry for several reasons. For one, they don’t understand lending on an intangible asset like a taxi medallion — you know they want to kick the tires on something like real estate or equipment,” Murstein says.

In New York, Medallion’s competition is limited to North Fork Bank — which prior to its 2006 acquisition by Capital One, held a small number of taxi medallion loans on its balance sheet — and one or two credit unions that also lend in the sector. In other cities, like Philadelphia for instance, Medallion is the only game in town.

Murstein says the nature of the taxi business means many lenders choose to avoid it. “These companies typically don’t have financial statements and bank regulators who want to see how they’re going to service the loan; they want to see strong financial statements,” Murstein says. “What’s more, a lot of these customers don’t even speak English and banks are not accustomed to dealing with minority entrepreneurs like we are. We’re very open to working with people who come to this country with no money in their pocket and just the dream to own their own business, and we provide that opportunity for them.”

At first, he considered acquiring an established firm. “We didn’t want to make the mistake that banks often make, which is pay two- or three-times book value for something and then have the management and ownership walk away and we’re left holding the bag. So we hired Gerry [Grossman] and his whole management team away from another bank.”

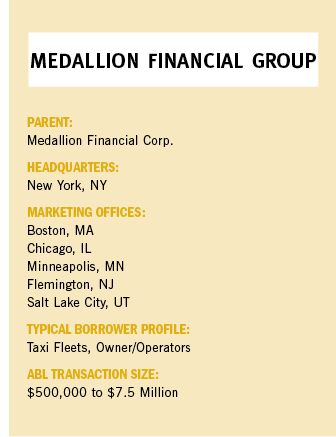

In 1998, Medallion Business Credit was founded to provide asset-based loans to commercial businesses. The company serves a diverse customer base that includes manufacturers, distributors, food processors and finance companies. Murstein says Medallion Business Credit specializes in funding “under the radar” deals, ranging in size from $500,000 to $7.5 million, secured by the borrower’s accounts receivable and inventory. Since its founding, the unit has expanded from a staff of two, to comprise 19 employees at two separate facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Grossman, who serves as president of Medallion Business Credit, says he started in asset-based lending when it was known simply as “commercial finance.”

After the business he ran with his father and brother was sold in 1973, Grossman stuck around for a while before deciding to try his hand in the legal profession. But his days as an attorney would be limited. In 1990, Grossman was approached by New York’s Sterling Financial with an offer to join the company’s ABL unit. He eagerly rejoined the field and spent four years at Sterling before jumping ship to help a friend, at Long Island’s Continental Bank, establish an ABL unit.

In less than two years time Grossman says he built Continental Business Credit’s portfolio to $20 million, attracting the attention of Reliance Federal Savings Bank, which bought out Continental Bank in 1997. After a short stint with Israel Discount Bank, Grossman and his partner, Connie Mitchko, moved to Medallion.

Grossman says a key to the unit’s success is he and Mitchko’s approach to customer service. “We thrive on relationships — Connie and I know every account, we visit with them, we field examine — we’re very hands on with the people we deal with,” he says.

Beyond ABL, Medallion operates Medallion Capital, which was set up in the 1990s to make subordinated loans to small- and medium-sized manufacturers, retailers, food service providers and other companies. The company secures its loans with liens on the borrower’s assets and receives warrants or other types of equity participation in order to offset the additional risk assumed by the loan structure.

The company also operates Medallion Bank, an FDIC-insured industrial bank located in Salt Lake City, UT, which has helped the company address increasingly stringent cost of funds issues.

The strategy seems to be working. In a time when the entire financial services industry is lamenting a dearth of liquidity, Murstein says he’s looking to expand. “We have a lot of excess capital these days. We’re always on the lookout for new lines of business to either buy existing companies or find good people to hire and go into new niche businesses,” Murstein says. “We’re always trying to find new lines of businesses. The reason we’ve been so successful is we’ve been good partners.”

No tags available