About the Study: What’s In, What’s Out

The words, numbers and graphs illustrate who is building aircraft now and who will be in ten years. The numbers represent only the value of deliveries; they exclude RDT&E and the generally more lucrative after-market support business. Additionally, they exclude other aerospace business done by companies involved, (e.g., Raytheon’s recent divestiture of its aircraft unit serves as an example of this.) Lastly, the report is oriented much more toward the civil sector with only summary notes on the military component.

Summary of Findings

Industry Trends & Themes

Secular Differences

Industry Trends & Themes

The world’s aircraft industries are enjoying great times. The market has enjoyed strong growth since 2003, and the expansion looks set to continue to 2008, and possibly beyond.

This growth is broadly spread over all major industry segments. Indeed, this is the first simultaneous civil/military market upturn in more than 20 years. Yet this diversity of growth is not shared by all players, implying change in the industry’s structure.

Segments & Growth

About two-thirds of the aircraft industry’s business volume is driven by civil markets. Therefore, it’s not surprising that the current boom began in 2003, as the world’s air transport industries began recovering from the great market shock brought about by the 9/11 terror attacks. This civil market recovery was boosted by military market growth, which also predictably began after those terror attacks.

The first year of the boom — between 2003 and 2004 — saw a respectable 5.7% growth rate. This was followed by 8.3% between 2004 and 2005. Teal Group is forecasting a strong 8.9% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2005 and 2008.

While we are also forecasting an aircraft market peak in 2009, this is a conservative outlook, based on a slowing economic growth in the coming 1-2 years and on a plateau in defense spending. It’s entirely possible, however, that industry growth will continue into 2010.

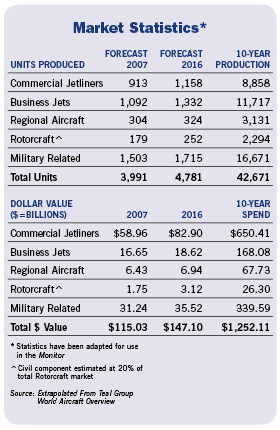

Our forecast calls for the value of new build aircraft deliveries to exceed $145 billion annually by 2016, up from just over $90 billion in 2005.

Breaking down these numbers by segment, commercial jet transports play a dominant role, at least in terms of volume. In 2007, jetliner and regional aircraft revenues account for about 60% of the total industry, and revenues from these markets will come to more than $700 billion in the 2007–2016 forecast period.

As for the other markets, business jets are a distant second, worth about one-fourth as much as jetliners and regional transports ($168 billion over ten years). Fighters are third, accounting for $157 billion in revenue. Rotorcraft, an 80% military segment, is fourth, comprising $132 billion in forecast revenue. The other segments (military transports, special mission aircraft, turboprop general aviation aircraft and trainers) together provide a total of almost $77 billion. The piston-powered general aviation industry, sadly excluded by this forecast, would barely register on our chart.

The aircraft industry has persistent and remarkable barriers to market entry. Just before this article was written, Sino-Swearingen succeeded in delivering its first production SJ30 light business jet. This development followed more than 20 years of slow, frequently confounded development efforts. But Sino-Swearingen’s modest success as a small, independent market entrant is quite remarkable. Since 1960, only one other all-new company — Embraer — has succeeded in entering the market for jet-powered aircraft.

There might be one or two additional new players entering the industry in the coming two years. The new breed of Very Light Jets (VLJs) offers an unusual combination of high-growth rates and relatively low capital requirements. But even if the most optimistic VLJ projections are borne out, the total value of these aircraft will still be relatively small — less than 10% of the business jet market by revenue (our forecast calls for them to comprise 5%). In short, any successful new VLJ players will be minor industry actors.

In addition to high barriers to entry, the aircraft industry is also notably concentrated. The top ten companies — Boeing, The European Aeronautical, Defense and Space company (EADS), Lockheed Martin, Bombardier, BAE Systems, Finmeccanica, Dassault, Embraer, Textron (Cessna and Bell Helicopter) and General Dynamics’ Gulfstream unit account for more than 85% of industry revenues.

There are no signs of any technological or market game-changers that would catapult any minor players into this elite group of industry leadership. In fact, this industry has seen several notable market exits over the past years. BAE Systems, after the sale of its 20% Airbus holding to EADS, has followed a clear path away from aircraft and towards other defense systems.

Yet this market concentration is somewhat deceptive. Although prime contractors are only increasing their dominance at the top end, they are also increasing their outsourcing. While 50-60% of the value of an aircraft has always been outsourced (engines, avionics, systems, interiors, etc.), primes are increasingly seeking to partner with second tier companies on major airframe structures. The primes are seeking to spread risk and costs, and focus on top end product integration and marketing.

As a result of this airframe outsourcing trend, the industry has seen the growing power of subcontract players specializing in aircraft structures. This industry too is relatively concentrated. The major players — Vought Aircraft, Finmeccanica and Japan’s Mitsubishi, Kawasaki and Fuji Heavy Industries — have been joined by Spirit AeroSystems, spun off by Boeing and now owned by private equity firm Onex. All of these increasingly important players are in high-cost production areas, implying barriers to entry that are just as severe as in the prime contractor arena.

Interestingly, the second tier of airframe subcontractors largely comprises current and former aircraft manufacturers, finding themselves in a diminished position as prime contractors in the industry and looking for additional work. Stork’s Fokker unit, Saab and Kaman are the best examples of this trend.

Secular Differences

The U.S. — Surviving at the Top

The U.S. has long enjoyed an impressive aviation industry lead against all challengers. U.S. companies are far up the aircraft production learning curve, and benefit from the largest civil and military markets in the world. They know more about systems integration, marketing and financing than anybody else does. They are also superb at globalization, in terms of recruiting customers and selling aircraft. The U.S. government avoids the European mistake of providing money for capitalization, not technology development. And of course, the dollar remains the most important currency for aircraft purchases.

As a result, the U.S. share of the world aircraft industry remains quite secure. Since the U.S. is home to the most important fighter program in the world (Lockheed Martin’s F-35 joint strike fighter) and the two most important widebody jetliner programs in the world (Boeing’s 777 and 787), this market dominance will increase. We forecast its growth from 53% in 2006 to 54.8% in 2015.

Europe — Through Troubled Times

But Europe remains serious about defense and aerospace. European governments are finally funding several key defense programs, most notably Eurofighter, Dassault’s Rafale and Airbus’s A400M military transport. More controversially, they have also provided technology development money for new civil programs, most notably Airbus’s A380 and A340-500/600. Their reason is simple — while government industrial policies are generally losers, aerospace is a proven non-loser. It may not be as efficient as private sector business investment decisions, but it does create jobs, develop technology and enhance prestige.

Yet Europe is now going through a difficult transition phase. While technology development money is still flowing, European governments are less willing to provide equity, or to direct large banks and politically connected corporations to provide equity. Increasingly, companies like EADS are forced to look to private sources for investment money, a process that could stall their new product development efforts. Efforts to bring Airbus’s new A350 XWB to market are clearly complicated by this need for new investors.

Emerging (and Non-Emerging) Producers

Outside the U.S. and Europe, most countries are slowly getting the message that aviation is not an industry for dabblers, and that access to private capital is more important than a government mandate. Asia’s experience with homegrown aircraft is driving this message home.

Traditionally, emerging aircraft producing countries develop indigenous aircraft for two reasons. One is the national security rationale; the other is the industrial policy rationale. These are inadequate (and somewhat contradictory) reasons to develop an aircraft industry.

The national security rationale has been obviated because indigenous fighters are overpriced underperformers. Taiwan was allowed to purchase the Western fighters it wanted anyway, as can any country — the weapons industry is always going to be a buyer’s market. In short, countries that really care about national security will buy fighters built by an established and experienced producer.

The other rationale, industrial policy, is a relic of the bad old days of inefficient parastatal industries. Spend a lot of money, build a factory in the jungle, and hope people buy your planes at list price. Sell them at a loss when they don’t, and watch the money go to Western component suppliers while your country’s private sector is starved for capital. Brazil’s Embraer (before it was privatized) is the classic example. Indonesia’s IPTN, under the oligarchic leadership of B.J. Habibie, wanted to follow this path, but IMF restrictions shelved most of its programs. China’s ARJ21 program might just go ahead, but it would only succeed in proving why it shouldn’t be done.

These two rationales fail to provide an incentive to build indigenous aircraft. They are also contradictory. To build planes as part of an industrial policy, a small company needs outside capital; a single government cannot alone provide the money needed to make it happen. Yet selling a stake in this company to a foreign entity weakens the national security case; an indigenous firm making indigenous jet fighters cannot be owned by foreigners.

The best illustration of this contradiction is Embraer. The Brazilian government investigated the security implications of the sale of a share in the company to a French consortium led by Dassault. The sale needed to go through for Embraer to succeed with its ERJ 170/190 regional jet family; yet the sale also compromised Embraer’s status as a purely local military supplier.

The last important state-directed economies in the world are being forced to convert to market capitalism, or at least to head in that direction. As this process continues, national pride and market share will matter less than return on investment. And the incestuous relationship between governments and companies is breaking down, as in Europe.

So, we see few new entrants into the aircraft production industry. Some Asian countries seeking to build regional jets will find their techno-nationalist aspirations quashed by government austerity efforts and an increasingly free market world economic environment.

In short, the aircraft market may be growing. But this growth will increasingly benefit established companies that have experience, existing product lines and, most of all, access to capital.

As a result of these trends, our “Rest of World” percentage of aircraft manufacturing will shrink, from 11.2% in 2006 to 9.6% in 2015. A portion of this will go to Russian programs. We forecast very limited success (or at least survival) for the Tupolev Tu-204 jetliner (the Il-96 looks dead, though), and continued export success for the Sukhoi Su-27/30 fighter series. We do not forecast series production of the RRJ, but it has the best chance of any new emerging producer RJ.

Brazil’s Embraer, Canada’s Bombardier and Mitsubishi’s F-2 will account for most of the rest. The other non-American, non-European aircraft builders will decline.

No tags available